Click here to download this post

LONG-COVID SYNDROME

for patients

NL DePace, MD, FACC and J Colombo, PhD, DNS, DHS

INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 is a major pandemic that is worldwide and may cause significant symptoms and possibly hospitalization. About 80% have mild to moderate disease. However, among the 20% with severe disease, 5% develop a critical illness. There is a subset of patients, however, who will have lingering, persistent or prolonged symptoms for weeks or month afterwards, which we termed “Long COVID.” (It does have many other names.) This has extended the significant worldwide morbidity from this pandemic. It is estimated that about 10% of patients who tested positive for COVID-19 will remain ill beyond three weeks and a smaller proportion for months. This is a subset that constitutes the Long-COVID syndrome. Globally, there are estimated over 200 million confirmed cases of COVID-19. Although the majority of infected individuals recover, we still do not know the exact percentage that will continue to experience symptoms or complications after the acute phase of the illness is over.

While it is estimated that 10% will develop a chronic syndrome, or symptoms that are persistent, this statistic may actually increase. Since this is a new illness, we do not know the cause or characteristics of the long-term sequelae of someone who has recovered from acute COVID,. Not just the quality of life, including mental health, but the employment and productivity issues become paramount. In our experience, approximately 20% of people will exhibit symptoms for more than five weeks and 10% will have symptoms for more than 12 weeks.

DEFINING LONG-COVID

The acute phase of COVID-19 infected patients has been well described and may a have varying number of symptoms and intensity. The recovery from COVID-19 usually occurs at seven to ten days after the onset of symptoms in mild disease, but could take up to six weeks in severe or critical illness. However, it is believed that even when one is ill for 3-6 weeks, they are probably not actively contagious. Again, symptoms beyond 12 weeks is considered Long-COVID Syndrome.

What exactly is Long-COVID Syndrome? There are many definitions that have been offered. Basically, there are individuals who do not completely recover over a period of weeks. Since COVID-19 is a novel disease, there is still no consensus of the definition of Long-COVID-19 symptoms. One study [1] found that 20% of the reports of long-term COVID symptoms involved abnormal lung function, 24% involved neurological complaints and olfactory dysfunction, and 55% on specific widespread symptoms, mainly chronic fatigue and pain. Usually, three or more months past the acute COVID-19 infection, symptoms that last for at least two months and cannot be explained by alternate diagnoses, may fit this definition. These symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, cognitive dysfunction, and symptoms that affect the functional capacity of individuals with daily living. Symptoms may fluctuate, flare up or relapse over time. Long-COVID-19 may adversely affect multiple organ systems, which include the kidneys, lungs, pancreas and heart.

Many patients with Long Covid Syndrome require rehospitalization especially those with comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, Diabetes Mellitus, obesity, cancer and kidney disease. Fatigue and muscle weakness are by far the major symptoms followed by dyspnea and then pain and discomfort. Then there is anxiety and depression and impaired concentration. Insomnia and sleep disorders present with lower frequency. Chronic cough may persist and arthralgias and myalgias may be present. Chest pain, cognitive impairment, dizziness and headache are also symptoms but less common than the ones above. Persistent sore throat, palpitations, lack of smell, diarrhea, vomiting, fever, blurry vision, lack of taste, nasal congestion, anorexia, nausea, ringing in the ears and rash may be present but at a much lower prevalence.

Autonomic dysfunction, which is an imbalance between the Parasympathetic and Sympathetic nervous systems, seems prevalent in Long-COVID-Syndrome. Autonomic dysfunction may explain multiple system symptoms, including some or all of: depression, chills, weakness, diarrhea, musculoskeletal, palpitations, tachycardia, dryness, cognitive dysfunction, headache, dizziness, visual effects, and tinnitus. Mechanisms of Long COVID Syndrome, like chronic inflammation, autoimmune, or hormonal imbalance, may be perpetuated by autonomic dysfunction. Lingering Autonomic Dysfunction also presents with auto-immune-like symptoms.

It has been postulated that there are two stages of Long-COVID-Syndrome: 1) symptoms that extend beyond three weeks, but less than 12 weeks, which is more of a subacute phase; and 2) chronic COVID symptoms that extend beyond 12 months. An interesting diagram and timeline has been postulated [2], which shows that Short-COVID will generally last less than three weeks from onset of symptoms. Post-acute COVID, or subacute COVID will last from onset of symptoms approximately up to 10-12 weeks and chronic COVID will last from onset of symptoms beyond 12 weeks. See Figure 1. It would make sense to group the Post-Acute or Subacute COVID, which lasts from up to 10-12 weeks, and then chronic COVID, which lasts more than 12 weeks as Long COVID Syndromes. Here we are more concerned with those symptoms that last more than 12 weeks, the true long- or prolonged-COVID Syndrome.

Figure 1: Classification of long COVID. [27]

Sometimes individuals are fairly asymptomatic during the viral infection phase of COVID, and by the time they develop Long-COVID symptoms, we do not know when the initial infection occurred nor are we certain (no positive tests). When these individuals develop multiple symptoms consistent with a Long-COVID Syndrome, we oftentimes consider them as probable, or possible Long COVID Syndrome. The problem is not only in those who have persistent symptoms who have never tested positive for COVID, but similarly in individuals who had upper respiratory tract infections and had a negative COVID test and then developed long prolonged symptoms. The question must be asked, “Did they have a false-negative test performed too early or too late in the disease course?” Antibodies are unreliable as up to 1/5 patients do not seroconvert, and antibody levels decrease over time and by three months oftentimes are not measurable. Not only is the symptom-load important with Long-COVID-Syndrome, but the economic cost to society, as 1/3 people in one survey did not return to their job for up to three weeks after being COVID-positive. In addition, given the similarity between Long-COVID Syndrome and Autonomic Dysfunction, and the ability of psychosocial stress to trigger symptoms of Autonomic Dysfunction further blurs the distinction between Long-COVID and Autonomic Dysfunction.

MULTIPLE ORGAN SYSTEMS INVOLVED

Long-COVID-Syndrome involve hyperinflammatory and hypercoagulable states that affect all organ systems. It reflects a dysfunction of the Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE 2) pathway. ACE-receptors are present in virtually every organ system. Workup consisting of pulmonary function tests, chest X-rays, six minute walk tests, pulmonary embolism workups (when needed), echocardiograms (even serially), and (at times) high resolution CT scans (to assess for fibrosis) should also be considered. These will be discussed under the Pulmonary section. Hematological assessment may lead to extending anti-coagulants against clots and high-risk survivors. A neuropsychiatric screening for anxiety, posttraumatic stress, sleep disorders, depression, cognitive impairment, memory abnormalities and other factors associated with brain fog is important. A neuropsychiatric screening should include a full autonomic dysfunction test, especially in patients with orthostatic intolerance symptoms and chronic fatigue syndromes. If there are renal function abnormalities, Nephrology follow-up and creatinine clearance determination with urinalysis evaluation may be needed. These may be performed in person or on virtual clinical visits. Next is a discussion of some of the various organ systems and how they are affected.

I. PULMONARY SYSTEM:

The pulmonary system, including the lungs, is the most commonly involved. Up to six months after hospitalization, pulmonary function abnormalities or structural changes may occur. Chronic complications, such as chronic cough, fibrotic lung changes also known as Long-COVID fibrosis or post-ARDS fibrosis, bronchiectasis and pulmonary vascular disease may occur [3] . Even if a person is asymptomatic, they may have CT scan abnormalities that are seen many months after infection has resolved. Approximately half of the patients with Long-COVID demonstrate chronic dyspnea. If COVID-19 leads to pulmonary fibrosis it may result in shortness of breath and the need for supplemental oxygen. There are also long-term risks of pulmonary embolisms and chronic pulmonary hypertension. Abnormal airway function may occur up to 11 months in severe COVID-19 infections [4]. Other abnormalities include abnormalities in total lung capacity, poor expiratory Vol at 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1 to FVC ratio, and small airway function abnormalities [5]. Mild cases usually have persistent chronic cough, which may be due to fibrosis, bronchiectasis and pulmonary vascular disease.

II: CARDIAC INVOLVEMENT:

Common cardiac problems may include labile heart rate and blood pressure and myocarditis and pericarditis. Many individuals have palpitations. Reports of arrhythmia are not significant. The treat of blood clots, including venous and arterial thrombotic disease and pulmonary embolism, is significant [6]. These structural abnormalities may manifest itself in Long-COVID Syndrome long after recovery of acute illness and predispose to arrhythmias, breathlessness, and acute coronary events, such as heart attacks and chest pain syndromes.

Myocardial injury is the most common abnormality detected with acute COVID infection. It is usually detected even when patients are asymptomatic with no cardiac symptoms with elevated cardiac troponin levels [7]. Further research is ongoing as to whether this myocardial injury pattern, even when subclinical, may lead to increased arrhythmias and heart failure in the long-term.

Echocardiographic studies have shown abnormalities with COVID, including right ventricular dysfunction 26.3%, left ventricular dysfunction 18.4%, diastolic dysfunction 13.2% and pericardial perfusion 7.2%. To what extent this is reversible in patients who go on to Long-COVID-Syndrome is not known [8]. In addition, sleep abnormalities and difficulties that reduce quality of life have been noted in Long-COVID-19 Syndrome patients. These may also adversely affect cardiac function, provoke arrhythmias, elevate blood pressure and exacerbate or cause hypertensive states. Chest pain and palpitations are status post-acute phase of COVID. Many of the chest pains and palpitations, which appear to be cardiology in etiology, are actually due to autonomic dysfunction, including the postural orthostatic tachycardia state. Therefore, the importance of not only doing cardiac imaging, ambulatory monitoring, stress testing, six-minute walk test, echocardiography and other noninvasive cardiac workup, but also autonomic testing, such as cardio-respiratory monitoring, HRV interval testing, beat-to-beat blood pressure with tilt testing and sudomotor testing may be useful in diagnosing autonomic nervous dysfunction.

Arrhythmias are noted Long-COVID but attention to the use of anti-arrhythmic drugs, Amiodarone for example, must be used carefully in patients who have fibrotic pulmonary changes after COVID-19 [9].

III: NEUROLOGICAL:

Encephalitis, seizures, and other conditions including prolonged brain fog may occur for several months after acute COVID infection [10]. Neuropsychiatric sequelae are often common and reported with many post-viral symptoms, such as chronic tiredness, myalgias, depressive symptoms, non-restorative sleep [11]. Migraine headaches, often refractory to treatment, and late-onset headaches have been presumed to be due to high cytokine levels. Loss of taste and smell may also persist for up to six months and longer on follow-up of patients. Brain fog, cognitive impairment, concentration, memory difficulties, receptive language, executive function abnormalities may also persist over a long period of time. This may be related to autonomic dysfunction and other factors [12],[13],[14]. Psychiatric manifestations are also common in COVID-19 survivors of more than one month. Approximately 15% have at least some evidence of depression and post-traumatic stress, anxiety, insomnia and obsessive compulsive behavior [15]. Again, Long-COVID often involves brain fog. This may involve mechanisms of cardiac deconditioning, post-traumatic stress or dysautonomia. Long-term cognitive defects may be seen occurring in up to 20%-40% of patients [16],[17],[18]. The association between Long-COVID-Syndrome and brain fog may be the result of the autonomic dysfunction, specifically Sympathetic Withdraw [19], and the associated decreased cerebral perfusion [19, 20]. It is postulated that high catecholamine levels may lead to paradoxical vasal dilatation and increased activation of the Vagus nerve that may result even in syncope and also sympathetic activity withdraw [21].

Autonomic dysfunction has been noted to be significant. Patients with orthostatic tachycardia and inappropriate sinus tachycardia may benefit from heart rate management including beta-blockers [22] and other autonomic therapies [personal observations]. The most frequent neurological long-term symptoms in patients were myalgias, arthralgias, sleeping troubles and headaches [23].

Muscle wasting and fragility are often seen prolonged. This is because COVID-19 when it is severe may cause catabolic muscle weakness and feeding difficulties [24]. Symptoms consistent with orthostatic hypotension syndrome and painful small fiber neuropathy were reported in as short as three weeks and as long as three months [25, 26, 27].

Treatment of autonomic nervous systems disorders involves exercise with both aerobic and resistant elements in a graded fashion that oftentimes begin with recumbent exercises, “low and slow” [28]. Fluid and electrolyte repletion is required. Avoiding exacerbating factors, such as prolonged sitting and warm environments is recommended. Some counter maneuvers and isometric exercises, compression garments especially up to the waist, or abdominal binders are recommended. Pharmacological treatment that may involve many different regimens may be prescribed, such as volume expanders (e.g., Fludrocortisone or Desmopressin) may be used along with vasoactivation (e.g., Midodrine or Mestinon). If there are prominent hyperadrenergic symptoms, Propranolol, Clonidine, Methyldopa or other beta-blockers may be considered, especially for a postural orthostatic tachycardia response.

Autonomic dysfunction involving gastrointestinal, urinary, pupillomotor (e.g., light sensitivity) and erectile dysfunction were more represented than non-neurological symptom groups. Other prominent autonomic dysfunctions in these post-COVID individuals included secretomotor and sweating abnormalities in about half the study population and thermoregulatory alterations. Autonomic dysfunction has been reported in up to 63% of patients having survived a COVID-19 infection

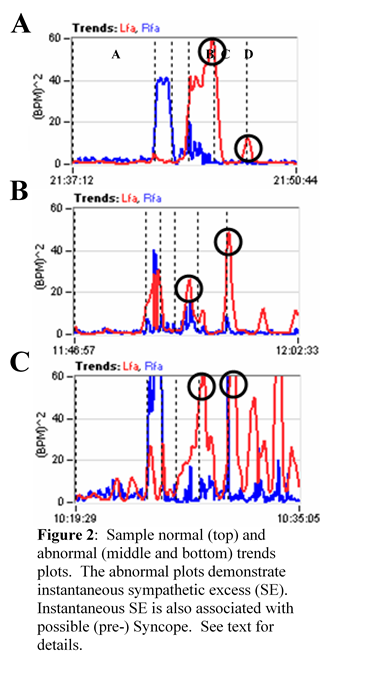

Chronic fatigue syndrome or Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, also known as post-infective syndrome, has been commonly recognized in the Long-COVID Syndrome [29, 30, 31]. Fatigue at three weeks post symptoms may occur in 13-33% of patients. There are many factors responsible which include sleep disturbances, autonomic dysfunction with sympathetic predominance, endocrine disturbances, abnormalities of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, reactive mood disorders and depression and anxiety. Findings therefore concluded that chronic fatigue post Long-COVID Syndrome is multifactorial. In fact, in the cohort at our autonomic clinic we have found significant disturbances in Cardiorespiratory and HRV testing in patients with chronic fatigue with Long-COVID-Syndrome with abnormal autonomic responses, including sympathetic withdraw (associated with orthostatic dysfunction) and vagal excess with postural change (associated with pre-syncope symptoms). Both autonomic dysfunctions are associated with poor cerebral and possibly coronary perfusion. These symptoms present regardless of whether they have drops in blood pressure, postural rise in heart rate or none of the above changes.

It is initially believed that SARS-COVID-19 causes sympathetic nervous system activation with catecholamine excess of activation in a sympathetic storm which activates the renin angiotensin system. Simultaneously, there is inhibition of the parasympathetic nervous system mediated anti-inflammatory effect, that leads to a decrease in neuro-vagal anti-inflammatory response and enhances the cytokine storm. This all leads to cardiopulmonary complications and COVID-19-induced dysautonomia [32]. The Parasympathetic responses reported above are found at rest. There is an abnormal Parasympathetic response to stress that may also occur [33], exaggerating the dynamic Sympathetic response to stress, thereby amplifying and prolonging the Sympathetically-mediated inflammatory, histaminergic, pain, and anxiety responses in a post-traumatic-like fashion.

IV. GASTROINTESTINAL SYMPTOMS ASSOCIATED WITH LONG-COVID SYNDROME.

At least 76% of patients had one of the GI sequelae symptoms 90-days after discharge of COVID-19, persisting to six months after disease onset [34]. COVID-19 may cause intestinal dysfunction due to changes in intestinal microbes and an increase in inflammatory cytokine, as well as Parasympathetic dysfunction. In the chronic phase the Gastrointestinal (GI) sequelae may include persistent anorexia, vomiting, abdominal pain along with diarrhea. GI upset may also be due to gastric and intestinal motility dysfunction due to COVID-induced Parasympathetic dysfunction. For example, diarrhea and abdominal pain may be due to excessive Parasympathetic activity causing overly-rapid GI motility.

Studies are currently evaluating the long-term consequences of COVID-19 on the GI system, including postinfectious, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and Dyspepsia.

V. HEMATOLOGICAL SEQUELAE OF LONG-COVID SYNDROME.

Late onset hematological complications with Long-COVID-19 has become an emerging medical problem for the hematologists. These include coagulopathy disorders, immune-thrombotic states, and hemorrhagic events. Long-COVID venous thromboembolism has been estimated to be less than 5% [35].

VI: KIDNEY DISEASE:

Patients that are extremely frail and have chronic comorbidities are at an increased risk for kidney disease and progression of kidney failure after infection of SARS-CoV-2.

VII: OLFACTORY and GUSTATORY ABNORMALITIES:

Recovery of the Olfactory and Gustatory system may last more than one month after the onset of smell and taste loss [36, 37]. Long-lasting effects on taste and smell are uncommon but have been noted in isolated cases.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF LONG COVID-19:

The mechanism behind the causation of Long-COVID Syndrome may be multifactorial. Oxidative Stress, due to the viral infection, may affect all systems compounded by hyperinflammation (a typical immune response to virus) with altered autonomic function (a result of a strong viral infection) as measured by cardiorespiratory monitoring. Oxidative Stress decreases the efficiency of Mitochondria, the energy producer in all cells, initiating the cascade of symptoms associated with Long-COVID.

TREATMENT IN LONG-COVID SYNDROME:

For the most part, supportive therapy for Long-COVID symptoms is a keystone and there is treatment for autonomic dysfunction. As mentioned earlier, volume expanders and vasodilators in addition to fluids, electrolytes, compression garments, and various exercise techniques have been prescribed for orthostatic intolerance symptoms. Omega-3 fatty acid and dietary supplementation may help resolve inflammatory imbalance [38]. L-arginine to boost Nitric Oxide production has been proposed [39]. Nitric Oxide maintains or improves the health and function of endothelial cells and benefits the immune system, especially in chronic fatigue states. Various antioxidants and zinc have been recommended to relieve Oxidative Stress. All of these therapies also effect proper autonomic function to help relieve Long-COVID symptoms [40]. Vaccination has been suggested as possibly a factor that may ease symptoms of Long-COVID. Most breakthrough infections were mild or asymptomatic, although persistent symptoms did occur. Mental health conditions may be treated with various psychological aides, such as cognitive behavioral therapy as well as antidepressants, including tricyclics.

LONG-COVID:

The symptoms of Long-COVID Syndrome may all be associated with autonomic dysfunction as measured with Cardio-Respiratory testing [40] and relieved with appropriate autonomic therapy based on the Cardio-Respiratory test [41].

REFERENCES

[1] Salamanna F, Veronesi F, Martini L, Landini MP, Fini M. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: The Persistent Symptoms at the Post-viral Stage of the Disease. A Systematic Review of the Current Data. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 May 4;8:653516. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.653516. PMID: 34017846; PMCID: PMC8129035.]

[2] Raveendran AV, Jayadevan R, Sashidharan S. Long COVID: An overview. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021 May-Jun;15(3):869-875. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.007. Epub 2021 Apr 20. PMID: 33892403; PMCID: PMC8056514.

[3] Fraser E. Long term respiratory complications of covid-19. BMJ. 2020 Aug 3;370:m3001. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3001. PMID: 32747332.

[4] Zhu M, Chen D, Zhu Y, Xiong X, Ding Y, Guo F, Zhu M, Zhou J. Long-term sero-positivity for IgG, sequelae of respiratory symptoms, and abundance of malformed sperms in a patient recovered from severe COVID-19. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021 Jul;40(7):1559-1567. doi: 10.1007/s10096-021-04178-6. Epub 2021 Feb 8. PMID: 33555444; PMCID: PMC7868306.

[5] Mo X, Jian W, Su Z, Chen M, Peng H, Peng P, Lei C, Chen R, Zhong N, Li S. Abnormal pulmonary function in COVID-19 patients at time of hospital discharge. Eur Respir J. 2020 Jun 18;55(6):2001217. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01217-2020. PMID: 32381497; PMCID: PMC7236826.

[6] Becker RC. Toward understanding the 2019 Coronavirus and its impact on the heart. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020 Jul;50(1):33-42. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02107-6. PMID: 32297133; PMCID: PMC7156795.

[7] Sandoval Y, Januzzi JL Jr, Jaffe AS. Cardiac Troponin for Assessment of Myocardial Injury in COVID-19: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Sep 8;76(10):1244-1258. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.068. Epub 2020 Jul 8. PMID: 32652195; PMCID: PMC7833921.

[8] Giustino G, Croft LB, Stefanini GG, Bragato R, Silbiger JJ, Vicenzi M, Danilov T, Kukar N, Shaban N, Kini A, Camaj A, Bienstock SW, Rashed ER, Rahman K, Oates CP, Buckley S, Elbaum LS, Arkonac D, Fiter R, Singh R, Li E, Razuk V, Robinson SE, Miller M, Bier B, Donghi V, Pisaniello M, Mantovani R, Pinto G, Rota I, Baggio S, Chiarito M, Fazzari F, Cusmano I, Curzi M, Ro R, Malick W, Kamran M, Kohli-Seth R, Bassily-Marcus AM, Neibart E, Serrao G, Perk G, Mancini D, Reddy VY, Pinney SP, Dangas G, Blasi F, Sharma SK, Mehran R, Condorelli G, Stone GW, Fuster V, Lerakis S, Goldman ME. Characterization of Myocardial Injury in Patients With COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Nov 3;76(18):2043-2055. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.069. PMID: 33121710; PMCID: PMC7588179.

[9] Kociol RD, Cooper LT, Fang JC, Moslehi JJ, Pang PS, Sabe MA, Shah RV, Sims DB, Thiene G, Vardeny O; American Heart Association Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Recognition and Initial Management of Fulminant Myocarditis: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020 Feb 11;141(6):e69-e92. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000745. Epub 2020 Jan 6. PMID: 31902242.

[10] Zubair AS, McAlpine LS, Gardin T, Farhadian S, Kuruvilla DE, Spudich S. Neuropathogenesis and Neurologic Manifestations of the Coronaviruses in the Age of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Review. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Aug 1;77(8):1018-1027. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2065. PMID: 32469387; PMCID: PMC7484225.

[11] Fauci, International AIDS Conference: YouTube 2020 and Nordvigas: Potential Neurological Manifestations of COVID-19: Neurology Clinical Practice 2020

[12] Henek A. Alzheimer’s Research Therapeutics Vol 1269, 2020.

[13] Ritchie K, Chan D, Watermeyer T. The cognitive consequences of the COVID-19 epidemic: collateral damage? Brain Commun. 2020 May 28;2(2):fcaa069. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcaa069. PMID: 33074266; PMCID: PMC7314157.

[14] Kaseda ET, Levine AJ. Post-traumatic stress disorder: A differential diagnostic consideration for COVID-19 survivors. Clin Neuropsychol. 2020 Oct-Nov;34(7-8):1498-1514. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2020.1811894. Epub 2020 Aug 26. PMID: 32847484.

[15] Mazza MG, De Lorenzo R, Conte C, Poletti S, Vai B, Bollettini I, Melloni EMT, Furlan R, Ciceri F, Rovere-Querini P; COVID-19 BioB Outpatient Clinic Study group, Benedetti F. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Oct;89:594-600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.037. Epub 2020 Jul 30. PMID: 32738287; PMCID: PMC7390748.

[16] Novac E. Neurologicals Vol 21, 100-276, 2021

[17] Miglis MG, Goodman BP, Chémali KR, Stiles L. Re: ‘Post-COVID-19 chronic symptoms’ by Davido et al. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021 Mar;27(3):494. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.028. Epub 2020 Sep 3. PMID: 32891765; PMCID: PMC7470728.

[18] Sakusic A, Rabinstein AA. Cognitive outcomes after critical illness. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2018 Oct;24(5):410-414. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000527. PMID: 30036191.

[19] Colombo J, Arora RR, DePace NL, Vinik AI. Clinical Autonomic Dysfunction: Measurement, Indications, Therapies, and Outcomes. Springer Science + Business Media, New York, NY, 2014.

[20] Stefano et.al. 2021

[21] Freeman R, Abuzinadah AR, Gibbons C, Jones P, Miglis MG, Sinn DI. Orthostatic Hypotension: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 11;72(11):1294-1309. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.079. PMID: 30190008.

[22] Raj SR, Black BK, Biaggioni I, Paranjape SY, Ramirez M, Dupont WD, Robertson D. Propranolol decreases tachycardia and improves symptoms in the postural tachycardia syndrome: less is more. Circulation. 2009 Sep 1;120(9):725-34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.846501. Epub 2009 Aug 17. PMID: 19687359; PMCID: PMC2758650.

[23] Salamanna F, Veronesi F, Martini L, Landini MP, Fini M. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: The Persistent Symptoms at the Post-viral Stage of the Disease. A Systematic Review of the Current Data. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 May 4;8:653516. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.653516. PMID: 34017846; PMCID: PMC8129035.

[24] Hosey MM, Needham DM. Survivorship after COVID-19 ICU stay. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020 Jul 15;6(1):60. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0201-1. PMID: 32669623; PMCID: PMC7362322.

[25] Dani M, Dirksen A, Taraborrelli P, Torocastro M, Panagopoulos D, Sutton R, Lim PB. Autonomic dysfunction in ‘long COVID’: rationale, physiology and management strategies. Clin Med (Lond). 2021 Jan;21(1):e63-e67. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0896. Epub 2020 Nov 26. PMID: 33243837; PMCID: PMC7850225.

[26] Hellmuth J, Barnett TA, Asken BM, Kelly JD, Torres L, Stephens ML, Greenhouse B, Martin JN, Chow FC, Deeks SG, Greene M, Miller BL, Annan W, Henrich TJ, Peluso MJ. Persistent COVID-19-associated neurocognitive symptoms in non-hospitalized patients. J Neurovirol. 2021 Feb;27(1):191-195. doi: 10.1007/s13365-021-00954-4. Epub 2021 Feb 2. PMID: 33528824; PMCID: PMC7852463.

[27] Novak E, Neurological Science, 2020.

[28] Fu Q, Vangundy TB, Shibata S, Auchus RJ, Williams GH, Levine BD. Exercise training versus propranolol in the treatment of the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Hypertension. 2011 Aug;58(2):167-75. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.172262. Epub 2011 Jun 20. PMID: 21690484; PMCID: PMC3142863.

[29] Townsend L, Dowds J, O’Brien K, et al.: Post–COVID-19 Respiratory Complications. Annals ATS;18(6), June 2021

[30] Poenaru S, Abdallah SJ, Corrales-Medina V, Cowan J. COVID-19 and post-infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a narrative review. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2021 Apr 20;8:20499361211009385. doi: 10.1177/20499361211009385. PMID: 33959278; PMCID: PMC8060761.

[31] Sandler CX, Wyller VBB, Moss-Morris R, Buchwald D, Crawley E, Hautvast J, Katz BZ, Knoop H, Little P, Taylor R, Wensaas KA, Lloyd AR. Long COVID and Post-infective Fatigue Syndrome: A Review. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 9;8(10):ofab440. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab440. PMID: 34631916; PMCID: PMC8496765.

[32] Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Qusti S, Alshammari EM, Gyebi GA, Batiha GE. Covid-19-Induced Dysautonomia: A Menace of Sympathetic Storm. ASN Neuro. 2021 Jan-Dec;13:17590914211057635. doi: 10.1177/17590914211057635. PMID: 34755562; PMCID: PMC8586167.

[33] Tobias H, Vinitsky A, Bulgarelli RJ, Ghosh-Dastidar S, Colombo J. Autonomic nervous system monitoring of patients with excess parasympathetic responses to sympathetic challenges – clinical observations. US Neurology. 2010; 5(2): 62-66.

[34] Weng J, Li Y, Li J, Shen L, Zhu L, Liang Y, Lin X, Jiao N, Cheng S, Huang Y, Zou Y, Yan G, Zhu R, Lan P. Gastrointestinal sequelae 90 days after discharge for COVID-19. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 May;6(5):344-346. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00076-5. Epub 2021 Mar 10. PMID: 33711290; PMCID: PMC7943402.

[35] Patell R, Bogue T, Koshy A, Bindal P, Merrill M, Aird WC, Bauer KA, Zwicker JI. Postdischarge thrombosis and hemorrhage in patients with COVID-19. Blood. 2020 Sep 10;136(11):1342-1346. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007938. PMID: 32766883; PMCID: PMC7483433.

[36] Addison AB, Wong B, Ahmed T, Macchi A, Konstantinidis I, Huart C, Frasnelli J, Fjaeldstad AW, Ramakrishnan VR, Rombaux P, Whitcroft KL, Holbrook EH, Poletti SC, Hsieh JW, Landis BN, Boardman J, Welge-Lüssen A, Maru D, Hummel T, Philpott CM. Clinical Olfactory Working Group consensus statement on the treatment of postinfectious olfactory dysfunction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021 May;147(5):1704-1719. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.12.641. Epub 2021 Jan 13. PMID: 33453291.

[37] Le Bon SD, Pisarski N, Verbeke J, Prunier L, Cavelier G, Thill MP, Rodriguez A, Dequanter D, Lechien JR, Le Bon O, Hummel T, Horoi M. Psychophysical evaluation of chemosensory functions 5 weeks after olfactory loss due to COVID-19: a prospective cohort study on 72 patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021 Jan;278(1):101-108. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06267-2. Epub 2020 Aug 4. PMID: 32754871; PMCID: PMC7402072.

[38] Weill P, Plissonneau C, Legrand P, Rioux V, Thibault R. May omega-3 fatty acid dietary supplementation help reduce severe complications in Covid-19 patients? Biochimie. 2020 Dec;179:275-280. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2020.09.003. Epub 2020 Sep 10. PMID: 32920170; PMCID: PMC7481803.

[39] Adebayo A, Varzideh F, Wilson S, Gambardella J, Eacobacci M, Jankauskas SS, Donkor K, Kansakar U, Trimarco V, Mone P, Lombardi A, Santulli G. l-Arginine and COVID-19: An Update. Nutrients. 2021 Nov 5;13(11):3951. doi: 10.3390/nu13113951. PMID: 34836206; PMCID: PMC8619186.

[40] Colombo J, Weintraub MI, Munoz R, Verma A, Ahmed G, Kaczmarski K, Santos L, and DePace NL Long-COVID and the Autonomic Nervous System: The journey from Dysautonomia to Therapeutic Neuro-Modulation, Analysis of 152 Patient Retrospectives. Submitted, 2022.

[41] DePace NL, Colombo J. Autonomic and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Clinical Diseases: Diagnostic, Prevention, and Therapy. Springer Science + Business Media, New York, NY, 2019.