Click here to download this post

The following is a rephrased excerpt from the book Clinical Autonomic and Mitochondrial Disorders by Doctors DePace and Colombo, Springer Publishers, Switzerland, 2019.

What is Vasovagal Syncope?

We are often asked by a patient to explain to them what Vasovagal Syncope is. One patient was in the emergency room after having an episode of passing out. She was in a warm room that was crowded and was standing for a long period of time. She became nauseous and had abdominal discomfort. Her vision began to become tunneled and her hearing faded. The next thing she knew was she was on the ground. She was brought to the emergency room where she was examined and found to be perfectly normal. She was given IV fluids and told she had a Vagal or Vasovagal episode and released. She presented to us with many questions. She had this for several instances and at times had to lie down to prevent an episode of fainting. She wanted to know what the mechanism of this so called Vasovagal Syncope was and how was it prevented.

Vasovagal Syncope is also known as a “simple fainting spell.” It is mediated by a neurological reflex within the body. What happens is one has a temporary loss of consciousness when a neurological reflex is activated. This reflex causes a sudden dilatation of the blood vessels of the legs where pooling of blood occurs in the lower extremities. It can also cause a slow heart rate sometimes down to 20 beats per minute, which can also lead to  reduced cardiac output. At times, both mechanisms can be operative, simultaneously. Oftentimes, Vasovagal Syncope is known as neurocardiogenic syncope or reflex syncope.

reduced cardiac output. At times, both mechanisms can be operative, simultaneously. Oftentimes, Vasovagal Syncope is known as neurocardiogenic syncope or reflex syncope.

What is the Vagus nerve?

One needs to first know what the Vagus nerve actually is. The Vagus nerve is the 10th cranial nerve in the body. There are 12 cranial nerves that emanate from the central nervous system. It is the longest nerve in the body. It has two branches of sensory nerve cells in the body and it connects the brain stem to the body. What it actually does is allow the brain to monitor and receive information about many of the various organs’ different functions in the body. The Vagus nerve is an intricate part of the autonomic nervous system, a part of what we term the Parasympathetic nervous system. This is a part of the nervous system that slows digestion, slows heart rate and causes the urinary bladder to contract or the GI tract to have motility. The Vagus nerve is also monitored for sensory activities and motor information for movement within the body. It basically links many organ systems to the brain.

The Vagus nervous system has Parasympathetic motor special sensory and sensory functions. For example, the sensory input from the throat, heart, lungs and abdomen is part of the Vagus nerve. It has special sensory functions in providing sensation behind the tongue at the back of the mouth and top of the throat – the gag reflex. In terms of motor, it provides an important function for the muscles in the neck responsible for swallowing and speech. As mentioned above, the Parasympathetic function is important for the urinary tract, digestive tract, respirations and heart rate functioning. The Vagus nerve activity is extremely important in our bodily functions, such as urination, defecation and sexual function. Many people who suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms have an abnormality of the communication between the brain and the gut with so called brain-gut connection, as the Vagus nerve delivers information from the gut to the brain, and then back again through the motor branches connected to the gut muscles to move the stomach and intestines – this is the source of “butterflies” in your stomach when you are nervous about something.

The Vagus nerve is also important in lowering heart rate and blood pressure. When it becomes overactive it can prevent the heart rate from pumping blood to the brain, which can occur with Vasovagal Syncope. Excess in Vagus activity intermittently can cause loss of consciousness.

Testing and Treatment of Vasovagal Syncope

While tilt-table testing is often considered the test of choice for differentiating Vasovagal Syncope, the simple placement of the patient on the tilt-table already treats the patient. Strapping the patient on the table stimulates the Sympathetic nervous system and the patients do not become symptomatic. P&S Monitoring tests for Vagal or Parasympathetic Excess (PE) without the need for tilt-table and is often more revealing. Furthermore, the Orthostatic Dysfunction of POTS or other orthostatic types of fainting where the blood pressure drops because blood pools in the leg due to a failure of the Sympathetic nervous system, and the PE of Vasovagal Syncope are not differentiated by tilt-table. As a result, some do not believe they may co-exist. Yet they are caused by dysfunctions in two different branches of the autonomic nervous system. P&S Monitoring is the only technology that is able to objectively quantify Parasympathetic activity, without assumption or approximation, and therefore, reliably and repeatable document and differentiate Vasovagal Syncope as well as chronic PE.

Chronic PE may include Vasovagal Syncope, but whereas Vasovagal Syncope is episodic or even recurrent and patients act and appear normal between episodes, Chronic PE is persistently symptomatic with persistent or chronic fatigue being the typical chief complaint. Chronic PE involves: difficult to control BP, blood glucose, hormone level, or weight, difficult to describe pain syndromes (including CRPS), unexplained arrhythmia (palpitations) or seizure, temperature dysregulation (both response to heat or cold and sweat responses), and symptoms of depression or anxiety, fatigue, exercise intolerance, sex dysfunction, sleep or GI disturbance, lightheadedness, cognitive dysfunction or “brain fog”, or frequent headache or migraine. If you consider the P&S nervous systems as the “brakes” and “accelerator” of your car, chronic PE is like “riding the brakes” or driving with your emergency brake on. When you “accelerate” you still go, but you need to over-rev the engine to get up to speed. As a result, little stresses are amplified, little worries become great fears, little concerns become anxieties, little touches become painful, little reactions become allergic, inflammatory reactions; all because the PE is forcing the Sympathetics to over-react. This is a source of fatigue and conditions like depression with anxiety (bipolar disease), attention deficit disorders, PTSD, and labile hypertension. There are many causes of chronic PE, mostly involving some sort of physical, mental or physiological trauma, including severe illness, surgery, injury, exposure, even numerous pregnancies. The good news is that PE, whether chronic or Vasovagal, is treatable.

Again, with Vasovagal Syncope, there is a sudden activation of the Vagus nerve. This is something that can occur episodically and recurrent. It also can be chronic and can cause flare-ups with crescendo phases to occur where people can go into almost Syncopal phases of fainting every day. Vasovagal Syncope can be precipitated by emotional stress or standing upright for long periods of time, or even prolonged sitting. It is oftentimes situational and can be caused by a hot environment, coughing spells, a patient urinating (so called Micturition Syncope) emotions, eating a large meal, severe pain or ongoing chronic pain and alcohol. Autonomic testing with a tilt test or Parasympathetic and Sympathetic (P&S) testing is sometimes necessary to document Vasovagal Syncope. These tests can show the actual reflex occurring, where there is slowing of the heart, or a progressive early drop in blood pressure, which is gradual, and the onset is without symptoms. This is later followed by a rapid drop in blood pressure and finally a slow heart rate. As shown in our example above, Vasovagal Syncope is often preceded by a prodrome, which is nausea, excessive fatigue, sweating, diaphoresis, and other GI symptoms, such as abdominal pain or feelings of defecation. These prodromes should be recognized by the patient so they can lie down, elevate their legs on a box or a chair and avoid an overt attack of passing out.

We use medications to treat patients who go in to malignant phases, or who have frequent Vasovagal Syncope, but we do not normally give medications to those who only have it periodically or episodically. For the latter patients, we teach how to recognize it and deal with it and recognize the symptoms. We have them hydrated, take sufficient salt, and oftentimes wear compression stockings. Patients who have this extremely frequently or go into a very crescendo phase we will oftentimes give a drug called Midodrine, which will prevent venous pooling in the lower extremities. We also sometimes will give anticholinergic therapy. A common one we use is Nortriptyline at only a low dose at 10 mg a day (clinical doses for use as an anti-depressant is around 100 mg a day, at only 10 mg, the side-effects are minimal). There are other pharmacological agents that could be used, but these are the two major ones that we often work with. Volume expanders may be helpful in patients who have very frequent and recurrent episodes especially in a crescendo phase. We have Florinef to work in a short period of time, but we do not like to use Florinef chronically, or for longer periods of time due to its side-effects. It is also used in very low doses and appears to be synergistic with Midodrine.

Vasovagal Syncope usually results from the Vagus nerve, or the Parasympathetic nervous system, becoming overactive temporarily. The treatment of Vasovagal symptoms, however, as mentioned, is usually supportive, avoiding situations which may precipitate it such as, crowded rooms and warm environments. Patients usually will become very accustomed to these types of situations.

Vasovagal Syncope is different than a syndrome known as Vagal excess, or Parasympathetic Excess. In these disorders, the Parasympathetic nervous system as compared to the Sympathetic nervous system is often dominant. That is, the so called Sympathovagal Balance is in favor of a high Vagal tone or high Parasympathetic tone chronically. These patients usually do not faint often because they are chronically adjusted to this high Vagal tone. Rather, they have symptoms of fatigue, insomnia, migraine headaches, various chronic gastrointestinal ailments, depression with anxiety, and oftentimes muscle aches similar to what is seen in the so called fibromyalgia syndromes. Some patients hurt all over with this syndrome. We have noted that patients with dependencies oftentimes have a chronic Vagal state, but this is only observational data and has not been validated in any specific studies as to date. This is just an empiric observation. We will often treat these disorders with low-dose anticholinergic drugs and a low-and-slow exercise program, and if there is a significant stress factor, various stress reduction modalities are used. Patients with Vagal excess often appear to suffer from chronic fatigue although chronic fatigue can be caused by any autonomic system that perpetuates a lack of blood supply to the head, such as abnormalities of the Sympathetic system where there is actually withdraw or deficiency on standing where people have chronic brain fog and tiredness, or the so called Orthostatic Intolerance syndrome. Therefore, chronic fatigue is not just seen with Vagal excess syndromes but also in syndromes where there are Sympathetic deficiencies when patients remain in the upright position, and this is a complex area of ongoing research.

In summary, Vasovagal Syncope is an episodic disorder which can be treated just with situational avoidance, education and conservative lifestyle changes with hydration, salt and compression stockings, or in cases where it is more frequent or severe, pharmacologic agents for short periods of time, or even at long periods of time. For long periods of time, anticholinergic agents, such as tricyclics, Nortriptyline or even SSRIs or SNRIs have been proposed to be effective in various people. Each person is an individual and reacts differently to pharmacology and sometimes one has to empirically do trials of different agents to find which is more successful. A tilt test is extremely helpful in reproducing the symptoms and disclosing the mechanism of Vasovagal Syncope and P&S testing may document the mechanism as well without requiring all of the symptoms to be demonstrated. It differentiates this from orthostatic hypotension and other orthostatic disorders. P&S testing is a simple noninvasive test which analyzes heart rate variability together with respiratory activity in response to the patient sitting and relaxed followed by a quick postural change to standing and then standing quietly, can be done in an office setting to document that the patient has a predisposition to Vasovagal Syncope disorder. Of course, the clinical history is the most important thing and just with that alone a diagnosis is usually made oftentimes in the emergency room after a patient presents with the sudden onset of fainting.

Vasovagal Syncope is a benign problem and has a good prognosis. Rarely are pacemakers put in, but these are usually in people older than 40, and there is significant controversy as to their efficacy. A cardiologist or an electrophysiologist will carefully have to analyze each person who has severe Vasovagal Syncope recurrent in a case-to-case basis to see if potentially a pacemaker will be helpful. In our experience, they are rarely helpful when put in young patients who have malignant Vasovagal Syncope, but in some older patients they may be beneficial and have actually stopped these episodes. But, again, this is a very variable situation.

One has to consult their physician if they have frequent episodes of what they believe is Vasovagal Syncope for proper treatment and oftentimes if it is quite profound, they will need to seek the results of an Autonomic physician specialist.

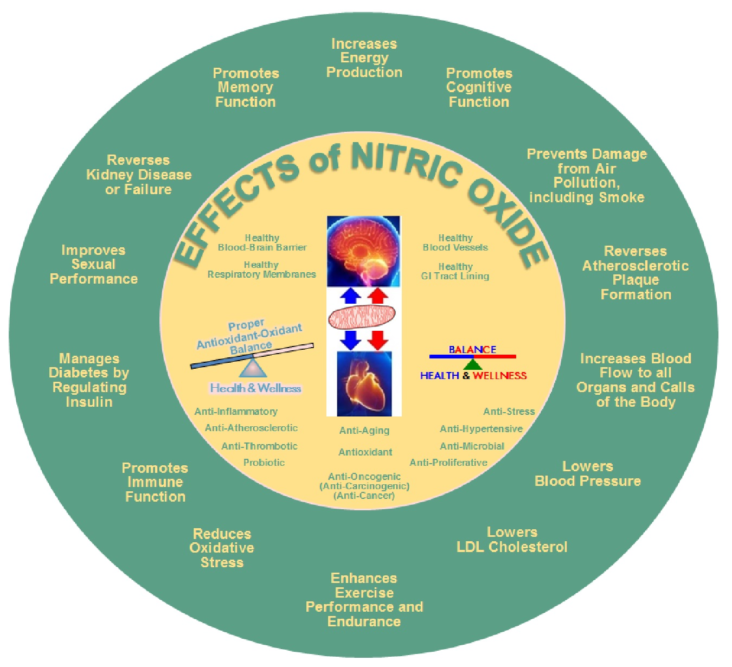

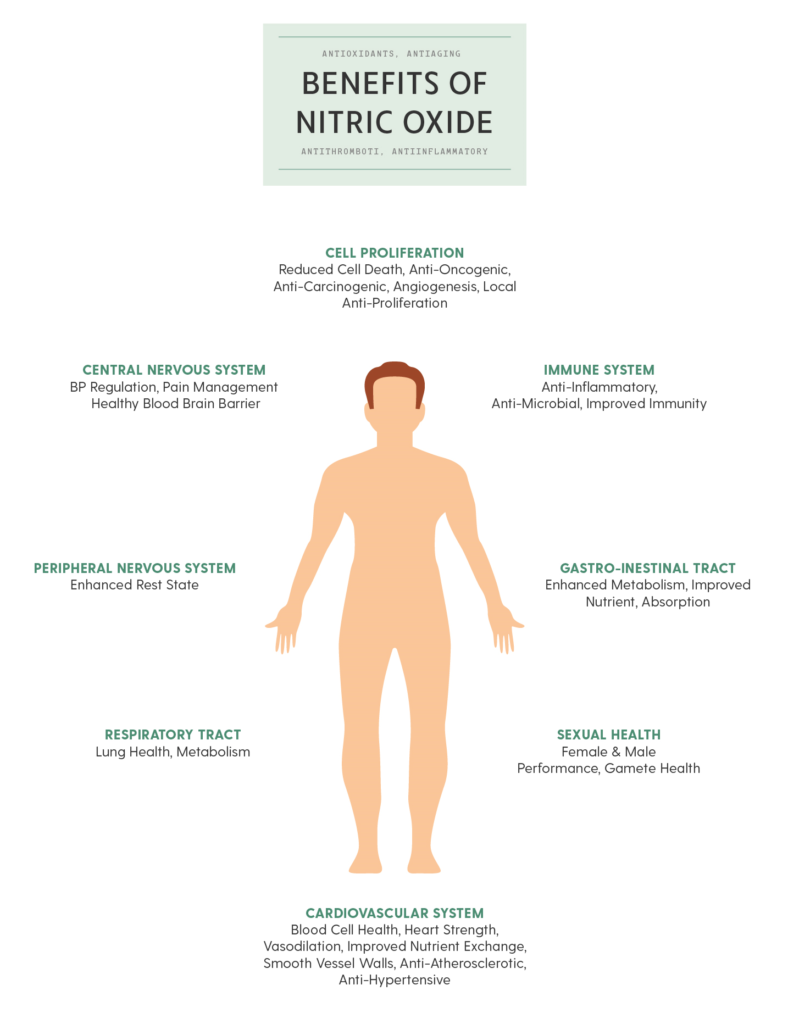

Nitric oxide is an important signaling molecule in the human body. It is very important in supporting mind-body wellness. Nitric oxide is a signaling molecule that helps all the cells communicate with each other in the body. It also regulates blood flow, aids in blood pressure regulation and activates the immune system.

Nitric oxide is an important signaling molecule in the human body. It is very important in supporting mind-body wellness. Nitric oxide is a signaling molecule that helps all the cells communicate with each other in the body. It also regulates blood flow, aids in blood pressure regulation and activates the immune system.

between the two (SB = S/P, known as Sympathovagal Balance) that is the key. Again with the car analogy, even if you have no brakes and no accelerator (you are very old or very sick) you may still roll down hill; even then if you cannot stop you crash. A normal ratio of Sympathetic to Parasympathetic is approximately 1.0 (SB = 1.0 is perfect balance). If SB is high, indicating that the Sympathetics are much more reactive than the Parasympathetics, this may exaggerate or amplify all Sympathetic responses. For example, little stimuli may become painful, little stresses may cause anxiety, little allergic reactions may become rashes or hives (significant histamine reactions). Insufficient Parasympathetic activity with excessive Sympathetic activity (a typical result of persistent stress, including psychosocial stress) may suppress the immune system, over stimulate the production of oxidants leading to excessive oxidative stress, raise blood pressure, promote atherosclerosis, cause persistent inflammation, accelerate diabetes, promote atherosclerosis, and accelerate the onset of heart disease, kidney disease, or dementia.

between the two (SB = S/P, known as Sympathovagal Balance) that is the key. Again with the car analogy, even if you have no brakes and no accelerator (you are very old or very sick) you may still roll down hill; even then if you cannot stop you crash. A normal ratio of Sympathetic to Parasympathetic is approximately 1.0 (SB = 1.0 is perfect balance). If SB is high, indicating that the Sympathetics are much more reactive than the Parasympathetics, this may exaggerate or amplify all Sympathetic responses. For example, little stimuli may become painful, little stresses may cause anxiety, little allergic reactions may become rashes or hives (significant histamine reactions). Insufficient Parasympathetic activity with excessive Sympathetic activity (a typical result of persistent stress, including psychosocial stress) may suppress the immune system, over stimulate the production of oxidants leading to excessive oxidative stress, raise blood pressure, promote atherosclerosis, cause persistent inflammation, accelerate diabetes, promote atherosclerosis, and accelerate the onset of heart disease, kidney disease, or dementia. normal function of aging, it is a risk indicator and the risk is significantly higher if the SB is abnormal, especially if SB is high indicating Sympathetic Excess. Ways to keep the sympathetic nervous system from becoming overactive or excessive include lifestyle changes, such as meditation, yoga, Tai Chi, or other forms of mild to moderate exercise. Various exercises can train the sympathetic nervous system not to become overactive and may also be good stress reducers.

normal function of aging, it is a risk indicator and the risk is significantly higher if the SB is abnormal, especially if SB is high indicating Sympathetic Excess. Ways to keep the sympathetic nervous system from becoming overactive or excessive include lifestyle changes, such as meditation, yoga, Tai Chi, or other forms of mild to moderate exercise. Various exercises can train the sympathetic nervous system not to become overactive and may also be good stress reducers. with POTS or orthostatic hypotension disorders) we generally begin with recumbent exercises, such as a recumbent bicycle, a rowing machine, or swimming (see insert, left). In the worst cases we recommend stating with exercises that including lying on the floor with your feet up on the bed or couch or the like and moving your lower legs like you are walking (see insert, left). In fact, a rowing machine is probably the best exercise initially for patients with

with POTS or orthostatic hypotension disorders) we generally begin with recumbent exercises, such as a recumbent bicycle, a rowing machine, or swimming (see insert, left). In the worst cases we recommend stating with exercises that including lying on the floor with your feet up on the bed or couch or the like and moving your lower legs like you are walking (see insert, left). In fact, a rowing machine is probably the best exercise initially for patients with  volume. Stroke volume is the amount of blood your heart pumps with each beat. Stroke volume is very important, since patients with these disorders often have low stroke volumes which means their hearts are not pumping enough blood to the brain while you are upright (sitting or standing).

volume. Stroke volume is the amount of blood your heart pumps with each beat. Stroke volume is very important, since patients with these disorders often have low stroke volumes which means their hearts are not pumping enough blood to the brain while you are upright (sitting or standing).