Click here to download this post

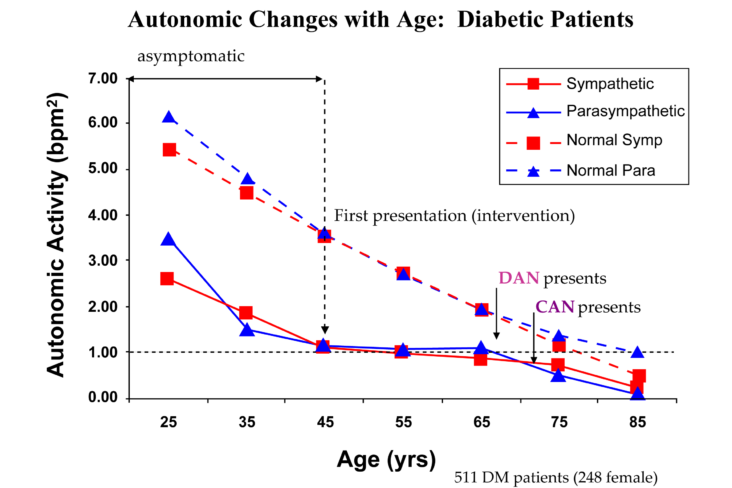

SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19 or Coronavirus) is a severe, acute, respiratory syndrome infection that involves the lungs and the immune system. The major clinical feature is Respiratory Distress Syndrome, and one key complication is Acute Cardiac Injury [1]. COVID-19 is a self-limiting infection and the strength of the immune and respiratory systems is critical in overcoming the infection and surviving the potential morbidity and mortality risks associated with the infection. Several comorbidities have been reported as risk factors for unfavorable prognosis in patients with COVID-19. The most common comorbidities that influence the outcome of COVID-19 patients are Cardiovascular Disease (CVD), Diabetes Mellitus type 2 (DMT2), Hypertension, Malignancy and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), among others, especially pulmonary disorders. Smoking and other factors that may compromise the lungs have also emerged as risk factors associated with a worse outcome. For example, China, which is one of the hardest-hit countries, has the vast majority of its population living in densely populated cities in which there have been significant amounts of construction, and the majority of their heat and electricity comes from burning fossil fuels, especially coal. This has been the condition for a number of years. On a visit to a number of their larger cities over a number of weeks in 2014, many of its citizens, especially the younger adult population, were already wearing masks to protect themselves from the heavy particulate pollution. In other words, by the time of the COVID-19 outbreak, it is reasonable to assume that the population of China was already respiratory-compromised to some degree.

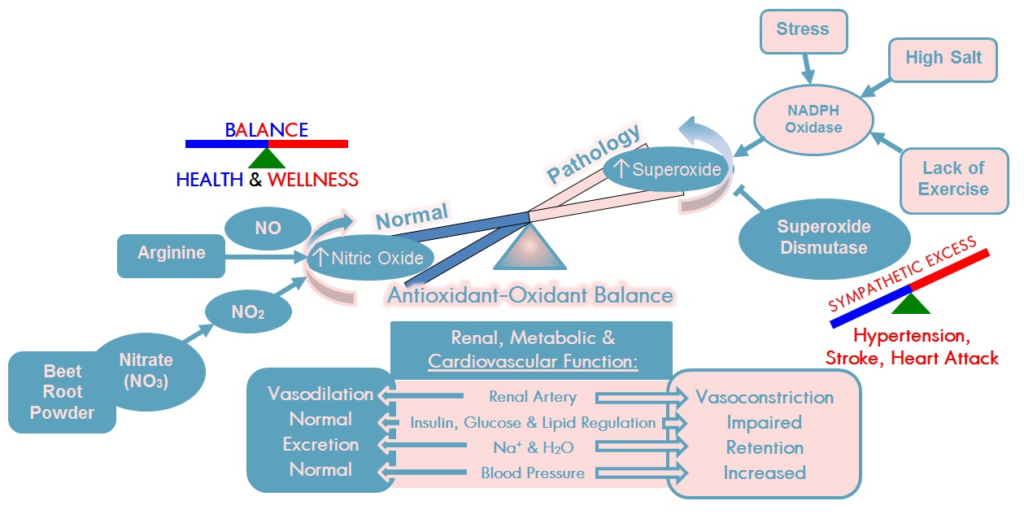

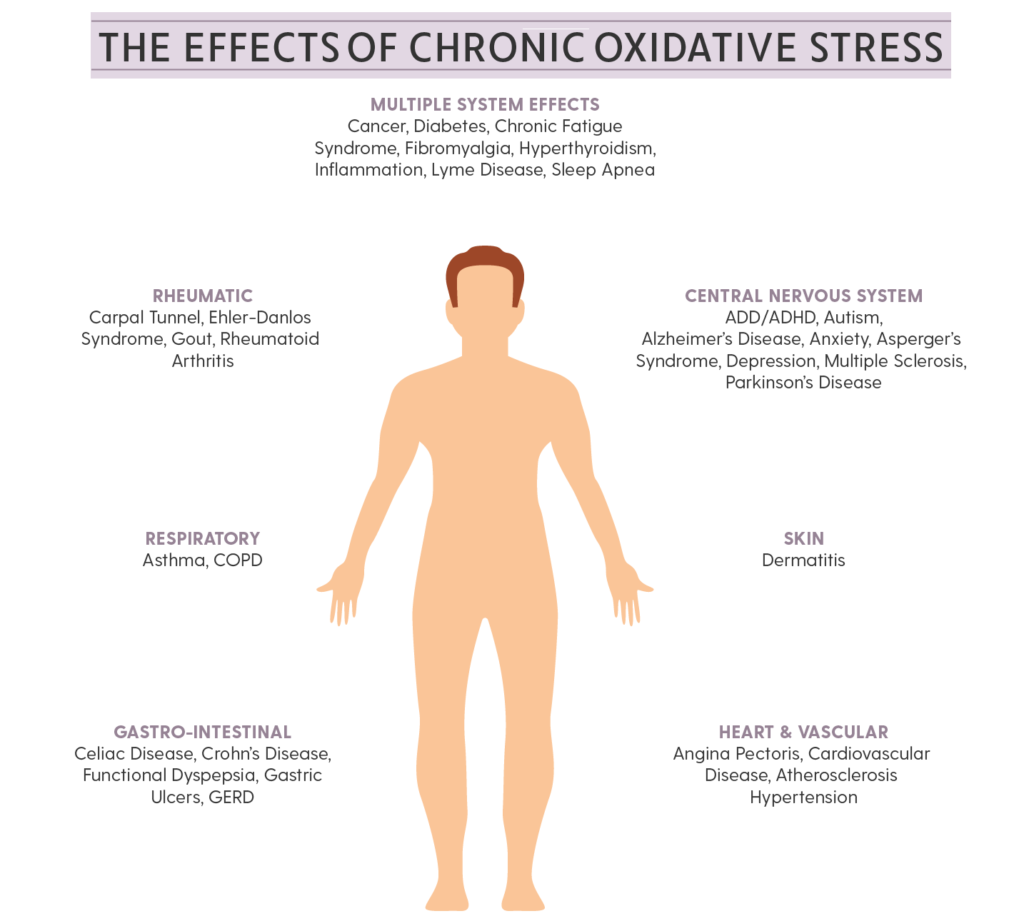

As commented [2], it has been shown that oxidative stress is associated with the same diseases (including CVD and DMT2 [3]) that increase the risk of a severe outcome from COVID-19. Oxidative stress is a condition of imbalance between the release of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and the endogenous antioxidant capacity of an individual’s system. It is also well known that smoking can induce cellular oxidative stress while it depletes antioxidants through various mechanisms [4],[5]. Studies have shown that antioxidant deficiency leads to increased sensitivity to even mild oxidative stress, while altered activity and levels of antioxidants have been recognized as markers of inflammation [6]. For example, and specifically for the Respiratory System, dysregulation of Glucose 6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase leads to a greater risk for protein glycosylation [7], a process that plays an essential role in promoting viral pathogenesis, including COVID-19 [8,[9],[10]. This example suggests that antioxidant therapy may help to treat, and perhaps prevent, SARS infections, including COVID-19, as well as Influenza.

It has been demonstrated [11] that human lung epithelial A549 cells with lower G6PD activity (via RNA interference) have a 12-fold higher viral production when infected with human coronavirus 229E, which shares a sequence similarity with COVID-19 and clinically resembles it, compared to control cells [11,[12]. Antioxidants may at least provide heart protection for COVID-19-infected individuals, based on the oxidative stress theory [13]. According to recent clinical reports, the therapeutic time for COVID-19 infection is much longer than 14 days, but long-time viral stimulation is prone to suddenly elicit intensive immunological reactions, cytokine storm, and immune-cell infiltration. However, some immunocytes, especially Macrophages and Neutrophils, can produce numerous Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) [13,[14],[15].

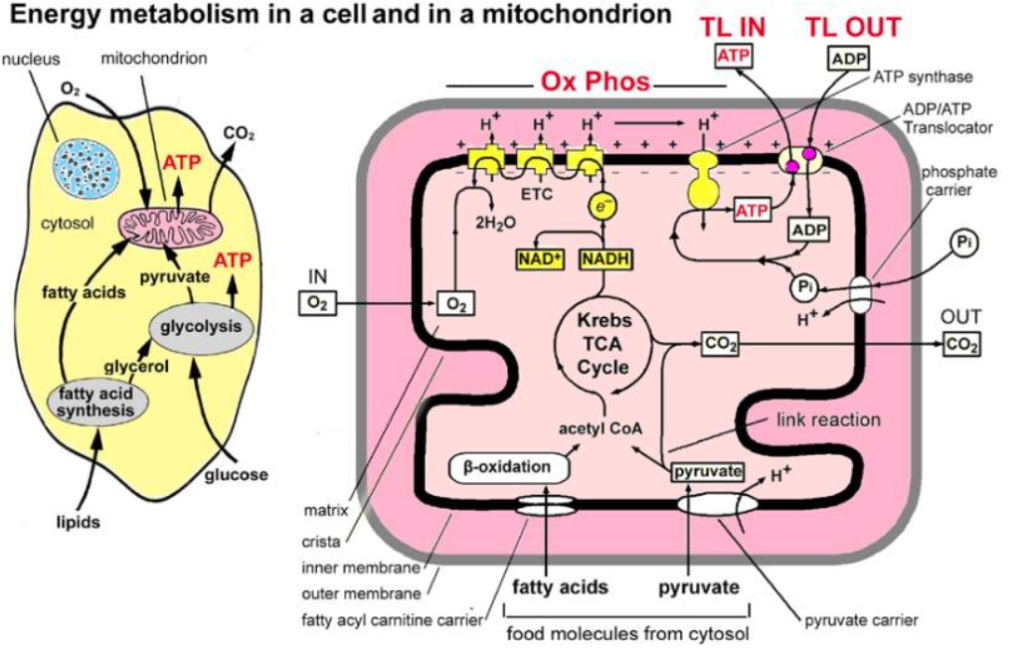

A certain level of ROS is important for regulating immunological responses, clearing viruses, and general health. It is part of the first line of defense by the immune system. Together with fever, Oxidants (like ROS) are used to “burn” the invading “trash” (i.e., foreign or excessive bacteria, molds, mildews, viruses, etc.) that enters your body every moment. The immune system collects the Oxidants and dumps them on the invading trash to kill them by oxidizing cellular proteins, membrane lipids, Mitochondria, and even DNA and RNA, etc. Meanwhile, the body brings in the Antioxidants to “put out the fire” once the “trash” is burned to protect the healthy tissue. However, excessive ROS (such as with illness, cancer, or Psychosocial stresses – including mental and physical stresses) will cause excessive oxidative stress, overwhelming the body’s reserve of Antioxidants, resulting in sickness and, in the extreme, death. This is why, in general, it is good to have a healthy Antioxidant reserve, and this is best built up through exercise and diet and, in those at risk, with additional nutraceuticals to supplement.

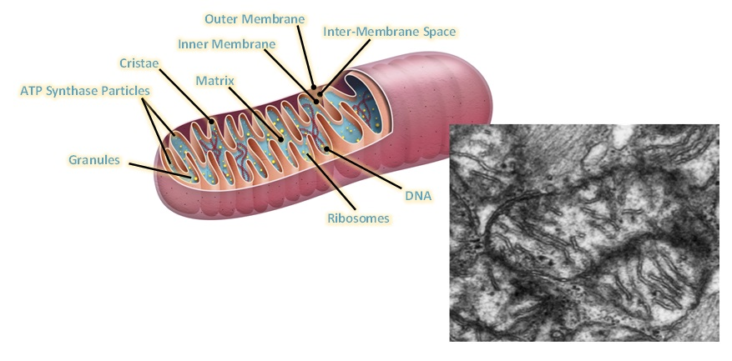

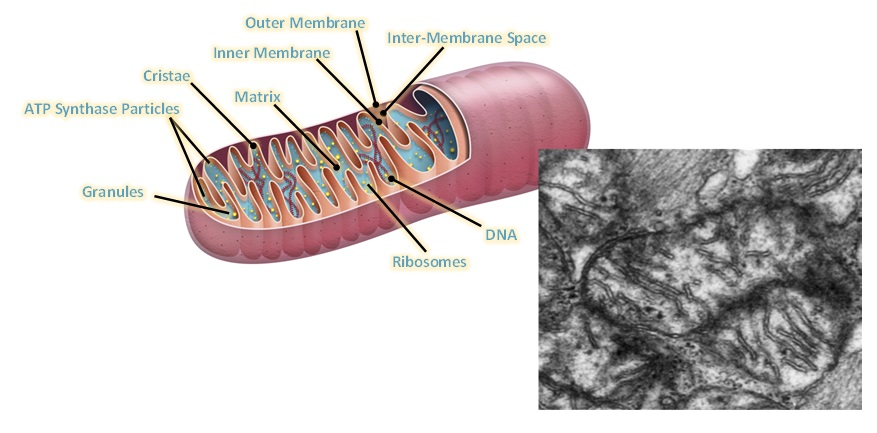

Oxidative stress may quickly destroy not only virus-infected cells, but also normal cells in the lungs, heart, nerves, and kidneys, resulting in multiple organ failure. Lungs are susceptible because they are constantly exposed to the outside. The heart and nerves are susceptible because they contain the greatest number of Mitochondria of all the cell-types in the body. Ironically, Mitochondria (the power plants of the body) are the greatest natural producers of ROS in the body (think of ROS and oxidants as the “pollution” from the power plants, however, in the case of the body these “pollutants” are used for good, to help the body, under normal conditions). The kidneys are susceptible because their job is to filter out the toxins from the blood, therefore, they exist in a highly toxic environment. Thus, a healthy Antioxidant reserve helps to prevent illness and, if ill, helps to treat illness, just like with colds, when people consume additional amounts of Vitamin C, a well-known antioxidant, to help rid themselves of the virus that caused the cold.

Thus, a potential antioxidant therapy could be proposed to alleviate the respiratory, cardiogenic, and other casualties caused by COVID-19. For example, inexpensive medicinal Antioxidants include Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid) and Vitamin E. These work through their reductive Hydrogen atoms react with ROS and then produce nontoxic water [16]. Plant-derived molecules (similar to ancient Chinese medicine), such as Curcumin (aka., Turmeric), may have potential antioxidant efficacy. These well-known Antioxidants and others (e.g., Vitamin A, Glutathione, Resveratrol, Omega-3 Fatty Acids, proper daily intake of water – 48 to 46 oz, etc.) are known to be made more potent through recycling with either Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) or Co-Enzyme Q10 (CoQ10). While ALA and CoQ10 are arguably the most powerful Antioxidants the body naturally makes, they increase their strength and the strength of the other Antioxidants by redirecting them away from the kidneys for another pass through the body. ALA tends to be specific for nerves, helping to protect the Mitochondria in the nerves to prevent the nerves from weakening, thereby preventing or relieving the neurological symptoms of illnesses, including viruses, like lightheadedness, malaise, cognitive and memory difficulties, fatigue, etc. CoQ10 tends to be specific for the heart, helping to protect the Mitochondria in the heart to prevent the heart from weakening, thereby preventing or relieving the cardiological symptoms of illnesses, including viruses, like low blood pressure, lightheadedness, fatigue, etc.

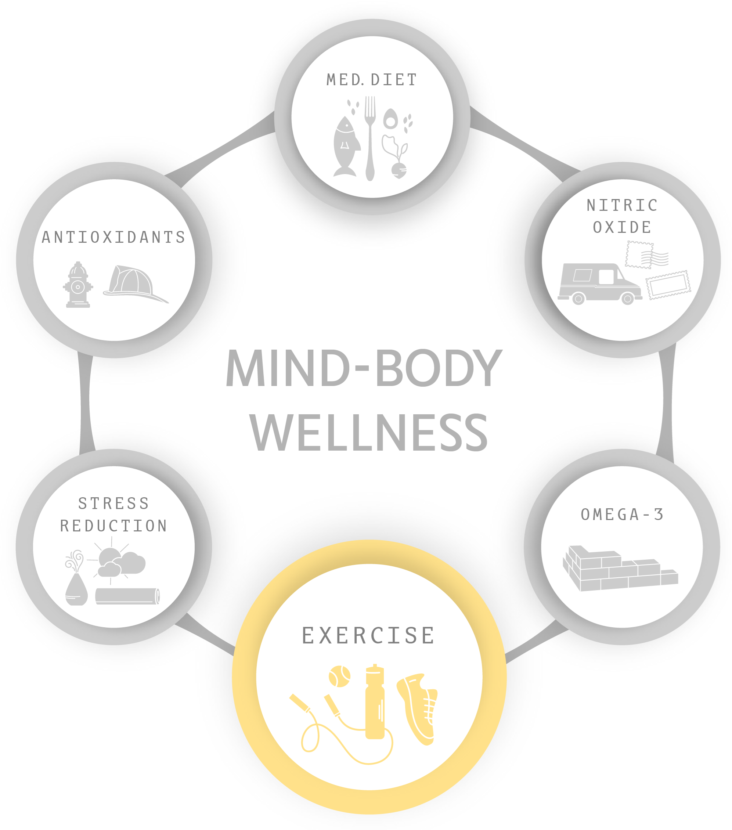

These Antioxidants also help to reduce chronic inflammation [6] which serves to exacerbate the effects of viruses, especially in the lungs as with SARS viruses (including COVID and Influenza). These Antioxidants are helped with Nitrates (dietary and supplemental) to boost the production of Nitric Oxide in the body. Nitric Oxide performs multiple functions in the body, including as an Antioxidant and an Anti-inflammatory, and it helps to prevent or relieve Atherosclerosis to improve heart health. Nitric Oxide also helps to detoxify the body, reducing the prevalence of Oxidants, including ROS. Nitric Oxide may be supplemented through L-arginine (which is limited by the body’s needs to produce it), L-Citrulline and L-Carnitine (which help the body to produce L-Arginine, and therefore is limited), and dietary Nitrates (the most well-known supplement at this time is Beet Root Extract Powder[1], and there are others). Dietary Nitrates are not limited and help to produce as much Nitric Oxide as is possible from the amount ingested. A healthy diet, like the Mediterranean Diet with multiple servings of fresh vegetables and fruits, helps to provide all of the above. The typical American Diet does not and may be contributing to Americans being more susceptible to illness, including COVID-19.

An optimal immune response depends on an adequate diet and nutrition in order to keep infection at bay [17]. For example, sufficient protein intake is crucial for optimal antibody production. Low micronutrient status, such as of vitamin A or Zinc, has been associated with increased infection risk. Frequently, poor nutrient status is associated with inflammation and oxidative stress. Dietary constituents with especially high anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capacity include vitamin C, vitamin E, and phytochemicals such as carotenoids and polyphenols (i.e., Resveratrol) and sources of other antioxidants (e.g., Glutathione, CoQ10 and ALA), as well as Nitrates and Amino Acids that support proper levels of Nitric Oxide production. Several of these can interact with transcription factors such as NF-kB and Nrf-2, related to anti-inflammatory and Antioxidant effects, respectively. Vitamin D in particular may perturb viral cellular infection via interacting with cell entry receptors such as Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 receptors (ACE2). Dietary fiber, fermented by the gut microbiota into short-chain fatty acids, and other sources of healthy Fatty Acids (e.g., Extra Virgin Olive Oil), have also been shown to produce anti-inflammatory effects, among other benefits for example, to help keep cell membranes pliable and resilient to infection. These and more are the benefits of a healthy diet with fresh, ripe produce (including extra helpings of dark green leafy vegetables – raw or lightly cooked, they still need to be green; not gray) and well-balanced proteins and fats which reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, thereby strengthening the immune system during any infection, including the COVID-19 crisis.

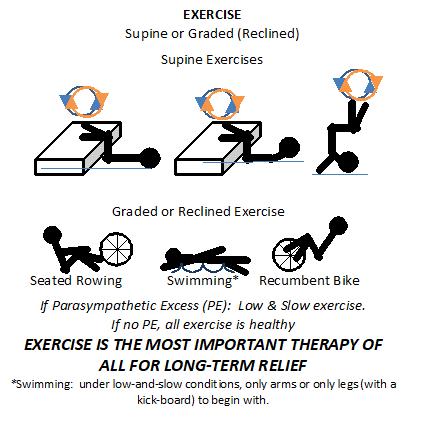

With all of the above regarding Antioxidants being said, arguably the most powerful and universal Antioxidant is EXERCISE [6,[18]]. Just one example is fever. As mentioned above, fever is part of the body’s first-line defense against illness and invading pathogens (viruses, bacteria, molds, mildews, allergens, etc.). While healthy human cells may survive between the temperatures of 98 and 104 °F, pathogens tend to be killed above 101.1 °F. Mild to moderate exercise for 40 minutes or more a day at least three times per week will simulate a fever (raise body core temperature to above 101.1 °F for at least 20 minutes). The simulated fever will help the body to eliminate any invading pathogens before they acquire a “foot-hold.” Read that: potentially kill off any COVID-19, Influenza, or other viruses, if exposed, before the pathogens (including the viruses) have a chance to infect you and make you sick. By mild to moderate exercise, we mean walking, gardening, playing with children, housework, calisthenics, or any activity that raises your heart rate and blood pressure above resting for a continuous 40 minutes and makes you sweat for at least 20 minutes. Of course, if you are healthy and fit, more strenuous exercise is also helpful to simulate fever. Exercise will also provide a number of other benefits, including: happier moods, reduced pain, better sleep quality, improved concentration and creativity, reduced stress levels and anxiety, maintained mental fitness, improved parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems function, stress reduction, improved heart and vascular health, improved neuroendocrine health, weight control (loss), reduced risk of DMT2 and metabolic syndrome, reduced cancer risk, stronger bones and muscles, reduced arthritis and other joint disorders, and promoted longevity (promotes living longer) [6].[2]

Exercise is demonstrate to have both short and long term effects by increasing aerobic capacity thereby increasing the function and strength of immune and respiratory systems, particularly those essential for overcoming COVID-19 infections and associated disorders. [18]. Exercise that increases aerobic capacity produces safe improvements in the function of immune and respiratory systems, particularly those specific for COVID-19 infections. These improvements are mediated through: (1) improved immunity by increasing the level and function of immune cells and immunoglobulins, regulating CRP levels, and decreasing anxiety and depression; (2) improved respiratory system functions by acting as an Antibiotic, Antioxidant, and Antimycotic[3], restoring normal lung tissue elasticity and strength; and (3) reducing the effects of risk factors such as DMT2,  Hypertension, and CVD, Obesity, and aging, to decrease COVID-19 risk factors, which helps to decrease the incidence and progression of the virus. To punctuate the issue, a recent review article [19] highlights the impact of “sedentarism” due to the COVID-19 home confinement. Even a few days of sedentary lifestyle are sufficient to induce muscle loss, neuromuscular junction damage and fiber denervation, insulin resistance, decreased aerobic capacity, fat deposition and low-grade systemic inflammation. Regular moderate exercise, together with a 15-25% reduction in caloric intake, are recommended for preserving neuromuscular, cardiovascular, metabolic and endocrine health, important in reducing the effects of the virus.

Hypertension, and CVD, Obesity, and aging, to decrease COVID-19 risk factors, which helps to decrease the incidence and progression of the virus. To punctuate the issue, a recent review article [19] highlights the impact of “sedentarism” due to the COVID-19 home confinement. Even a few days of sedentary lifestyle are sufficient to induce muscle loss, neuromuscular junction damage and fiber denervation, insulin resistance, decreased aerobic capacity, fat deposition and low-grade systemic inflammation. Regular moderate exercise, together with a 15-25% reduction in caloric intake, are recommended for preserving neuromuscular, cardiovascular, metabolic and endocrine health, important in reducing the effects of the virus.

A proper dose of Antioxidants may ameliorate respiratory, cardiac, and other system injuries of critically ill COVID-19-infected patients

Even after a serious infection, like from COVID-19, if the Antioxidant system was over taxed, the virus or infection will leave behind oxidative stress – at the cellular level. We emphasize “at the cellular level” because often times, the systems seem normal and healthy and all of the tests that most physicians order return normal, yet there are lingering symptoms and even disability, both mental and physical. The problem is two-fold. First, while the individual cells themselves are dysfunctional, the net sum total of their functioning still meets the minimum standards for “normal.” Second, the typical patient’s problem is not at rest (which is when most tests are performed – sitting or lying down) but when active. It is like a car with a full fuel tank, which idles just fine, but, due to a clogged fuel filter, cannot accelerate when needed. They look normal at rest, but are quickly fatigued when required to do work, either mental or physical. Again, Antioxidants, especially ALA, CoQ10, and EXERCISE, will help to relieve the oxidative stress and thereby relieve the fatigue and other lingering symptoms.

Currently, there is a lack of evidence regarding the exact role that Antioxidants play in COVID-19 infection. High-dose supplementation with Antioxidants, when given at an early stage of the infection, may prevent the spread of the virus in the body, thereby providing protective effects and reducing the severity of disease. This is proven to help in the other well-known SARS viruses including Influenza. To that end, traditional medicine products, supplements and nutraceuticals that are Antioxidants and anti-inflammatories are amongst the various additive treatments for COVID-19 under investigation [20].

ENDNOTES

[1] Not the portion of the beet that is typically eaten, the tuber, but the little root below the tuber.

[2] However, as always, an exercise regimen should be started under close physician supervision. The wrong types of exercise may do more harm than good, including increasing body fat (and thereby weight), fatigue, and pain due to the fact that the body is programmed to over-react to stresses. Under these conditions, the body sees exercise as stress and works to protect itself against the stress.

[3] An agent that is used against fungal infections.

REFERENCES

____________________

[1] Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al., Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China, Lancet 395 (2020) 497–506.

[2] Wang JZ, Zhang RY, Bai J. An anti-oxidative therapy for ameliorating cardiac injuries of critically ill COVID-19-infected patients. Int J Cardiol. 2020 Apr 6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.04.009 (Epub ahead of print).

[3] Moldogazieva NT, Mokhosoev IM, Mel’nikova TI, et al. Oxidativestress and advanced lipoxidation and glycation end products (ALEsand AGEs) in aging and age-related diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev2019;2019:3085756.

[4] Niemann B, Rohrbach S, Miller MR, et al. Oxidative stress and cardio-vascular risk: obesity, diabetes, smoking, and pollution: part 3 of a 3-part series. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:230e251.

[5] Wenham C, Smith J, Morgan R. Gender and COVID-19 WorkingGroup. COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet2020;395:846e848.

[6] DePace NL, Colombo J. Autonomic and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Clinical Diseases: Diagnostic, Prevention, and Therapy. Springer Science + Business Media, New York, NY, 2019.

[7] Jain SK. Glutathione and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase defi-ciency can increase protein glycosylation. Free Radic Biol Med 1998;24:197e201.

[8] Watanabe Y, Bowden TA, Wilson IA, et al. Exploitation of glycosyl-ation in enveloped virus pathobiology. Biochim Biophys Acta GenSubj 2019;1863:1480e1497.

[9] Lan J, Ge J, Yu J, et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2020;581:215e220.

[10] Gumustekin K, Cifttci M, Coban A, et al. Effects of nicotine and vitaminE on glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in some rat tissuesin vivo and in vitro. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2005;20:497e502.

[11] Wu YH, Tseng CP, Cheng ML, et al. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydroge-nase deficiency enhances human coronavirus 229E infection. J InfectDis 2008;197:812e816.

[12] Li Y, Liu B, Cui J, et al. Similarities and evolutionary relationships ofCOVID-19 and related viruses. arXiv 2020;2003. 05580 [q-bio.PE].

[13] Loffredo L, Martino F, Zicari AM, Carnevale R, Battaglia S, Martino E, et al., Enhanced NOX-2 derived oxidative stress in offspring of patients with early myocardial infarction, Int. J. Cardiol. 293 (2019) 56–59.

[14] Perrone LA, Belser JA, Wadford DA, Katz JM, Tumpey TM, Inducible nitric oxide contributes to viral pathogenesis following highly pathogenic influenza virus infection in mice, J. Infect. Dis. 207 (2013) 1576–1584.

[15] Imai Y, Kuba K, Neely GG, Yaghubian-Malhami R, Perkmann T, van Loo G, et al., Identification of oxidative stress and toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury, Cell 133 (2008) 235–249.

[16] Erol N, Saglam L, Saglam YS, Erol HS, Altun S, Aktas MS, et al., The protection potential of antioxidant vitamins against acute respiratory distress syndrome: a rat trial, Inflammation 42 (2019) 1585–1594.

[17] Iddir M, Brito A, Dingeo G, Fernandez Del Campo SS, Samouda H, La Frano MR, Bohn T. Strengthening the Immune System and Reducing Inflammation and Oxidative Stress through Diet and Nutrition: Considerations during the COVID-19 Crisis. Nutrients. 2020 May 27;12(6):E1562. doi: 10.3390/nu12061562. PMID: 32471251.

[18] Mohamed AA, Alawna M. Role of increasing the aerobic capacity on improving the function of immune and respiratory systems in patients with coronavirus (COVID-19): A review. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Apr 28; 14(4): 489‐496. Published online ahead of print,

[19] Narici M, De Vito G, Franchi M, Paoli A, Moro T, Marcolin G, Grassi B, Baldassarre G, Zuccarelli L, Biolo G, di Girolamo FG, Fiotti N, Dela F, Greenhaff P, Maganaris C. Impact of sedentarism due to the COVID-19 home confinement on neuromuscular, cardiovascular and metabolic health: Physiological and pathophysiological implications and recommendations for physical and nutritional countermeasures. Eur J Sport Sci. 2020 May 12:1-22. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2020.1761076. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32394816.

[20] Fauci AS, Lane HC, Redfield RR. Covid-19: Navigating the uncharted. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1268e1269.

Please, EXERCISE IS NOT A DIRTY WORD! It does not have to be drudgery. We are not talking about going to the gym and beating yourself up for hours. Perhaps a better description is “ACTIVE LIFESTYLE,” which may include exercise (in the sense of the current vernacular), but it should reflect the lifestyle of people before automobiles, elevators, television remotes, and cell phones. It can be a single (preferably daily) acute bout of physical exertion or muscular activity that expends energy above one’s basal or resting level – frequent movement of some sort. It is true, siting has become the “new smoking.” For those who are old enough, we are referring to a time before electronics, when play was not sitting around with computer games getting strong thumbs and weak bodies and communicating with someone was not done electronically developing stronger thumbs. People walked places or rode their bikes, children were outside walking, skipping, running, jumping, breathing fresh air and soaking in sunshine for their daily dose of Vitamin D. Adults would do house work, garden, yard-work, walk to the corner store, walk over to the neighbors to check on the children, or have a cup of coffee or tea and catch up on the news of the neighborhood, or simply play with the children at home, take the stairs or shop, etc. Life was not sedentary. Life included what we mean by exercise.

Please, EXERCISE IS NOT A DIRTY WORD! It does not have to be drudgery. We are not talking about going to the gym and beating yourself up for hours. Perhaps a better description is “ACTIVE LIFESTYLE,” which may include exercise (in the sense of the current vernacular), but it should reflect the lifestyle of people before automobiles, elevators, television remotes, and cell phones. It can be a single (preferably daily) acute bout of physical exertion or muscular activity that expends energy above one’s basal or resting level – frequent movement of some sort. It is true, siting has become the “new smoking.” For those who are old enough, we are referring to a time before electronics, when play was not sitting around with computer games getting strong thumbs and weak bodies and communicating with someone was not done electronically developing stronger thumbs. People walked places or rode their bikes, children were outside walking, skipping, running, jumping, breathing fresh air and soaking in sunshine for their daily dose of Vitamin D. Adults would do house work, garden, yard-work, walk to the corner store, walk over to the neighbors to check on the children, or have a cup of coffee or tea and catch up on the news of the neighborhood, or simply play with the children at home, take the stairs or shop, etc. Life was not sedentary. Life included what we mean by exercise. fever (20 minutes or more of exercise, three or more times per week helps to prevent disease before is starts); 2) Exercise is arguably the strongest antioxidant available and provides all of the benefits of antioxidants (like Vitamin C), including defeating (promoting the oxidation of) all types of infections: viral, bacterial, fungal, etc.

fever (20 minutes or more of exercise, three or more times per week helps to prevent disease before is starts); 2) Exercise is arguably the strongest antioxidant available and provides all of the benefits of antioxidants (like Vitamin C), including defeating (promoting the oxidation of) all types of infections: viral, bacterial, fungal, etc.

demonstrated. Urea Cycle dysregulation, Tricyclic Carboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle disturbances, and dysregulation of Amino Acid metabolism are also involved. Also, gut microbiota disturbances have been identified. In regard to Mitochondrial dysfunction, studies state that ATP8 levels have been both noted to be reduced and elevated, and resting ATP8 synthesis rates have been variable. However, studies on isolated Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells have shown that under stress such as Hypoglycemia there is inefficient ATP8 production in Chronic Fatigue patients but not in normal controls. This was demonstrated by Tomas and coworkers in 2017. Therefore, while resting ATP studies show that production may not be significantly abnormal in ME/CFS patients as compared with controls, it appears that under stressful situations, such as Hypoglycemia, the situation is different when one analyzes peripheral blood mononuclear cell ATP production. ATP is the energy molecule of the cell and of the body and is produced in the Mitochondria, which are the energy factories of the body.

demonstrated. Urea Cycle dysregulation, Tricyclic Carboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle disturbances, and dysregulation of Amino Acid metabolism are also involved. Also, gut microbiota disturbances have been identified. In regard to Mitochondrial dysfunction, studies state that ATP8 levels have been both noted to be reduced and elevated, and resting ATP8 synthesis rates have been variable. However, studies on isolated Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells have shown that under stress such as Hypoglycemia there is inefficient ATP8 production in Chronic Fatigue patients but not in normal controls. This was demonstrated by Tomas and coworkers in 2017. Therefore, while resting ATP studies show that production may not be significantly abnormal in ME/CFS patients as compared with controls, it appears that under stressful situations, such as Hypoglycemia, the situation is different when one analyzes peripheral blood mononuclear cell ATP production. ATP is the energy molecule of the cell and of the body and is produced in the Mitochondria, which are the energy factories of the body. Figure Legend: Schematic diagram showing various viral pathogens potentially associated with ME/CFS and possible molecular mechanisms altered by these pathogens that can contribute to ME/CFS development [[i]].

Figure Legend: Schematic diagram showing various viral pathogens potentially associated with ME/CFS and possible molecular mechanisms altered by these pathogens that can contribute to ME/CFS development [[i]].

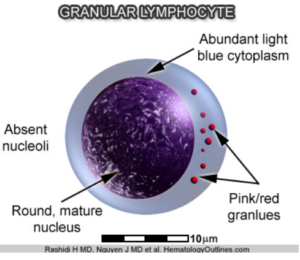

researched but has been performed on a subtype that is especially comorbid with Irritable Bowel Syndrome, which is seen in many Chronic Fatigue patients. Autoimmune evidence has been strengthened by the fact that there is a decrease in the natural killer cell cytotoxicity in patients with ME/CFS. Natural killer cells are Granular Lymphocytes which attack viruses and bacteria foreign to the body. In addition, the autoimmune evidence is supported by autoantibodies which have been noted against various transmitter receptors, both Muscarinic receptors and Beta receptors. A high incidence of these receptors has also been found in patients with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia. Specifically, autoantibodies against the Muscarinic and Cholinergic receptors #3 (M3) and autoantibodies against the Muscarinic and Cholinergic receptor #4 M4) are elevated in 20-30% of all patients suffering from ME/CFS. Other studies have shown Beta-1 Adrenergic Receptor Autoantibodies and Beta-2 Adrenergic Receptor Autoantibodies along with Alpha-1 Adrenergic Receptor Autoantibodies, the same autoantibodies which we find in a significant number of patients with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome.

researched but has been performed on a subtype that is especially comorbid with Irritable Bowel Syndrome, which is seen in many Chronic Fatigue patients. Autoimmune evidence has been strengthened by the fact that there is a decrease in the natural killer cell cytotoxicity in patients with ME/CFS. Natural killer cells are Granular Lymphocytes which attack viruses and bacteria foreign to the body. In addition, the autoimmune evidence is supported by autoantibodies which have been noted against various transmitter receptors, both Muscarinic receptors and Beta receptors. A high incidence of these receptors has also been found in patients with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia. Specifically, autoantibodies against the Muscarinic and Cholinergic receptors #3 (M3) and autoantibodies against the Muscarinic and Cholinergic receptor #4 M4) are elevated in 20-30% of all patients suffering from ME/CFS. Other studies have shown Beta-1 Adrenergic Receptor Autoantibodies and Beta-2 Adrenergic Receptor Autoantibodies along with Alpha-1 Adrenergic Receptor Autoantibodies, the same autoantibodies which we find in a significant number of patients with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome.

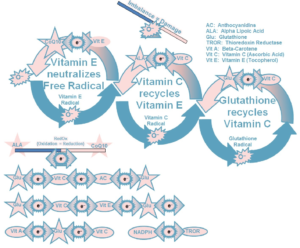

The body has natural Antioxidants to sequester, or neutralize, Free Radicals to prevent oxidative stress from injuring tissues and destroying cells. Natural Antioxidants include Vitamins A, C, & E, Glutathione, Selenium, Alpha Lipoic Acid (ALA) and Coenzyme Q-10 (CoQ10). Many scientists feel that ALA is the ideal antioxidant because it is both a lipid and water soluble (it can dissolve in both lipid and water environments) and can cross the Blood-Brain Barrier. It is absorbed rapidly through the Gastrointestinal (GI) tract high up in the digestive system and it is immediately available to neutralize free radicals quickly. It has also been shown to recycle Vitamin C and Vitamin E in the body. Vitamin C is only water soluble and Vitamin E is only lipid soluble. Because ALA is both liquid and lipid soluble, it can pass the Blood-Brain Barrier and increase available brain energy. Not only can ALA recycle Vitamin C & E but also Glutathione. Glutathione is probably the most important intracellular Antioxidant.

The body has natural Antioxidants to sequester, or neutralize, Free Radicals to prevent oxidative stress from injuring tissues and destroying cells. Natural Antioxidants include Vitamins A, C, & E, Glutathione, Selenium, Alpha Lipoic Acid (ALA) and Coenzyme Q-10 (CoQ10). Many scientists feel that ALA is the ideal antioxidant because it is both a lipid and water soluble (it can dissolve in both lipid and water environments) and can cross the Blood-Brain Barrier. It is absorbed rapidly through the Gastrointestinal (GI) tract high up in the digestive system and it is immediately available to neutralize free radicals quickly. It has also been shown to recycle Vitamin C and Vitamin E in the body. Vitamin C is only water soluble and Vitamin E is only lipid soluble. Because ALA is both liquid and lipid soluble, it can pass the Blood-Brain Barrier and increase available brain energy. Not only can ALA recycle Vitamin C & E but also Glutathione. Glutathione is probably the most important intracellular Antioxidant. Antioxidant and is synthesized within the Mitochondria and consists of three Amino Acids, Cysteine, Glutamic Acid, and Glycine. Glutathione is not easily absorbed orally and cannot pass through the Mitochondrial membrane so easily. Therefore, anything that preserves the body’s natural production of Glutathione and keeps the concentration up is valuable. This is where ALA comes in as a very important Antioxidant. It recycles Glutathione and replenishes the body’s stores. Glutathione is a very important component of several enzyme systems in the body that are organ-protective from disease. There is some data to suggest that ALA is also an excellent chelating agent and protects us from heavy metals, although this is beyond the scope of this discussion.

Antioxidant and is synthesized within the Mitochondria and consists of three Amino Acids, Cysteine, Glutamic Acid, and Glycine. Glutathione is not easily absorbed orally and cannot pass through the Mitochondrial membrane so easily. Therefore, anything that preserves the body’s natural production of Glutathione and keeps the concentration up is valuable. This is where ALA comes in as a very important Antioxidant. It recycles Glutathione and replenishes the body’s stores. Glutathione is a very important component of several enzyme systems in the body that are organ-protective from disease. There is some data to suggest that ALA is also an excellent chelating agent and protects us from heavy metals, although this is beyond the scope of this discussion.